|

POW-MIA: "WE WILL NEVER FORGET" "When one American is not worth the effort to be found, we as Americans have lost"  |

History of Rolling Thunder

|

Rolling Thunder®, Inc. History The Years of Rolling Thunder's They say the sound brings it all back. If you stand in Washington, D.C. the day before Memorial Day and face the Memorial Bridge, you will hear it for yourself. When it begins it's just a distant rumbling, more a feeling than a noise.

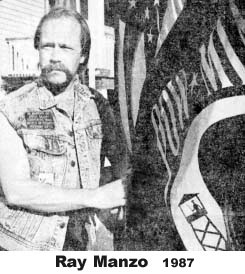

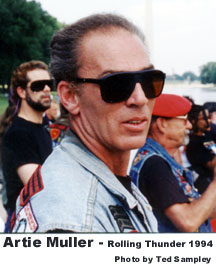

Then the bridge itself seems to tremble and something big shimmers on the distant horizon. They say there's only one thing on earth equal to the din of B-52s in carpet-bomb formation. They say it's the sound of Rolling Thunder's Run to the Wall. What began as a drive to champion what really happened to abandoned U.S. prisoners of war under the murky veil surrounding the Vietnam War has evolved into a uniquely American cause to protect and aid all U.S. military personnel then, now, and in the future. There's no denying the noise generated by more than 250,000 motorcycles riding wheel to wheel as they do each year in support of their mission is enough to get anyone's attention. But what's really impressive is the impact the group has had on a national and international level. To appreciate how far they've come, you really have to go back to where and how they got started. That would be a smoky little diner near Summersville, New Jersey in 1987. A couple of Vietnam vets had crossed paths when they discovered each was doing the same thing on their own. "We were just two guys going around putting up flags," recalls Artie Muller of his meeting at the diner with co-founder Ray Manzo. "It was Ray's idea to do the motorcycle run. As for the name, there's nothing that sounds more like the B-52's carpet-bombing than a large group of Harley-Davidsons!"

"I was in the U.S. Army," Muller, now Rolling Thunder president, states matter-of-factly. Today, it's no big deal to tell strangers your military affiliation. But Muller remembers clearly the very different world he and fellow vets returned to after serving in Vietnam. "People would spit on us. Literally. Some called us names like 'baby-killers.' Basically we were treated like hell. I know guys who came home and just went and hid out in the woods. "Most of us just came home and put our uniforms away. Didn't talk to anybody. Just tried to get back to a regular life. That was the best you could do. But there were guys who were, who still are, having a hard time with it." The sting of being shunned by the very nation they had gone to fight and lay down their lives for was bad enough. But the pain of learning how politics of war had betrayed them was far worse. "There were - so many guys - who went their first day into combat and got sent home in body bags the same day. They just weren't being trained what they needed to know to stay alive," Muller recalls. "I was combat infantry, Sergeant E-5. I extended my stay another three months to keep these guys alive - to train them, the guys just coming in, so at least they'd have a chance." For many, including American POW patriots left behind in captivity, the right to at least have a chance seemed to be a little too much to ask. In the aftermath of troop withdrawal, the government seemed more eager to save face than to salvage the lives of those who served. "Leave No One Behind" Muller can explain Rolling Thunder's history in a few well-chosen, heartfelt words: "We found out the U.S. government lied to everybody and we were very aggravated. We got involved in Washington passing bills to protect armed forces left behind after conflicts. We help servicemen get their VA benefits and steer them in the right direction to get the help they need."

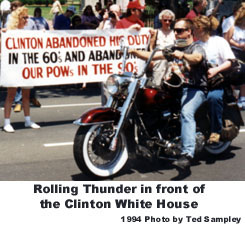

In the beginning, there was a march as well as the motorcycle run, to bring attention to the Rolling Thunder cause. Neither Muller nor Manzo were used to being the ones on the demonstration line, and had no clue the response they might have that first year. "None of us ever did anything like this before," Muller says of the first event. "We applied for the permits and got them OK. That part went pretty smoothly. But when we got there - we didn't know what to expect. We didn't know if anybody would even show up." Hearts soared when the first motorcycles appeared. Then more cycles came and kept on coming until some 2500 motorcycles joined in the unmistakable roar of unity. In addition, upwards of 5000 marchers showed up, too. The crowd, it turned out, wasn't just Vietnam vets, but ordinary civilians as well. It was as if the American populace, silent all those years, had suddenly found voice. The vets, who had served without thanks and suffered without support that day received a long overdue vote of confidence from a tardy nation. Suddenly, being a Vietnam vet was no longer a mark of shame, but a badge of honor. Out of the woodwork came droves of would be heroes claiming to have medals in a war they never fought, some even too young to remember. Despite the oddness of the 1980s turnabout, Rolling Thunder has never wavered from its cause. Muller cites the hero mentality as one he strives to overcome in dealing with vets who belatedly have to come to terms with a war without closure. "Veterans, all of them, did their part, whether they were in combat or not. Whether they were loading cargo in planes, trucking food into the guys or flying in supplies, they all deserve credit. I don't think it's right for guys to feel they weren't vital just because they maybe weren't in combat." After the first few events, the march portion of Rolling Thunder's demonstration was dropped, but the motorcycle motorcade continues to swell in rank and number. The year 2000 Memorial run included over 250,000 cycles and about 400,000 attendees in support of the group. Ask any serviceman how you close a military mission, and you'll hear the same words "Leave no one behind." It might have started out as a limited engagement to focus attention on those unaccounted for after Vietnam, but it's become much, much more. Rolling Thunder picked up the banner of accountability its government dropped and carries it with pride and honor into the 21st century. Timeline to Unity The birth of Rolling Thunder didn't take place in some upscale boardroom like most big organizations. It wasn't born on paper like many well intended goal-oriented missions. And it certainly wasn't the brainchild of Pentagon military minds at secret strategy sessions. Instead what has become one of the largest grassroots veterans' groups in history began silently, in the heart of a serviceman wanting only to do the right thing. When Ray Manzo came home from Vietnam in 1969, he carried with him more than the memory of a long costly war. Far from the 1st Marine Division, 7th Engineers, Bravo Company, 2nd Platoon where he served two years from 1968 to 1969, Manzo kept hearing an aching voice apparently ignored by top war strategists. What about us, it seemed to cry. What about us? What about us when the peace was signed? What about us - the ones who kept our promise to fight for freedom as long as we drew breath? What about our freedom? What about the nation's promise to us? It was that silent, collective cry of American GIs left behind that refused to die in his head that prompted Manzo in 1987 to try in some small way to make things right. He began writing letters. Not sure of how to make his idea reality, he sent the letters to anyone he thought might give a care. Soon people began to read the letters from the heart of the tough old Marine. Members of well-established vet organizations read them. Hard core biker club members read them. Newspaper editors tossed them in piles of letters to print, along with pothole complaints and letters of thanks to local firefighters. Many ignored the plea he voiced, or just nodded agreeably as they threw it out with the day's trash. But some didn't. In fact, a lot didn't. Among those who took the letters seriously were groups dedicated to helping POW/MIA families. Then one day Ray Manzo walked up to some vets manning several POW/MIA vigils near the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington and asked for help. His idea: Host a motorcycle run in the nation's capital to show the country and the world that abandoned American soldiers in Vietnam still mattered to their fellow servicemen and the country for which they sacrificed their freedom. From that day on, things began to happen. One guy he talked to that day was Walt Sides, Vietnam vet and retired Marine 1st sergeant. Sides, president of the non-profit Warriors Inc, also took him seriously and began seeking support to help make the run happen. Another was Bob Schmitt, head of the Camp Brandenburg POW/MIA vigil. Schmitt contacted the National Forget-Me-Not Association for POW/MIA's Inc. and ask its director John Parcels for help. Parcels, a retired major and former POW, who was released in March 1973 from a Vietnam POW camp, joined the effort. He secured the endorcement of other returned POWs including retired Air Force Col. Laird Gutterson, held POW in Vietnam for over five years and Larry Stark, a Navy industrial relations employee, also held POW in Vietnam for over five years. Retired Army Sgt. Maj. John Holland first laid eyes on Manzo while manning one of the POW/MIA vigils. Manzo's idea seemed just the thing his American Foundation for Accountability of POW/MIAs could sink its teeth into. Vigils like the one Holland operated took part in had just come into its own nationwide, but still needed something to grab public attention for the cause. Holland knew National Park Service regs and offered to navigate the sea of paperwork needed for such an endeavor. What better date for the event than on Memorial Day, when America honored the sacrifices of its soldiers throughout its long history of liberty and justice for all? As the plan came together, even its organizers were surprised by the widespread response the run inspired. Those conversations led to a meeting with Artie Muller, who served in the 4th U.S. Infantry Division during Vietnam. Manzo explained his vision to Muller over coffee at a diner in Summerville, New Jersey. As he listened to the impassioned Marine's words, Muller saw in Manzo's dream something vets could get a hold of and run with. And run with it they did. Pooling talents and resources, vets found a common cause they could all support. Muller started to work on getting transportation for interested participants, as well as needed permits for the motorcycle run. Four and a Half Seconds of Fame So it happened that a three day event for Memorial Day weekend 1988 took shape in recognition and remembrance of the more than 2,500 POW/MIAs from Vietnam's sad legacy. Even that long after the war, scattered sightings of live missing servicemen continued to be reported. They called it the Rolling Thunder Rally. By the time it was over, about 2,500 bikers had taken a stand by riding in defiant unity against what they saw as government disrespect and disregard for the fallen or captured in Vietnam. That amounted to roughly one biker for each missing American. News coverage of the 1988 Rolling Thunder Rally was short and sweet. If mentioned at all, it was condensed neatly into about 4 1/2 seconds of air time. Still, somebody saw it. At home, thousands of vets watched their brothers stand up to be counted, and resolved that the next chance they got, they'd do the same. Sure enough, the following spring, they got their chance. When James Gregory called for volunteers for a Run to the Wall, the response was overwhelming. The Vietnam Vets Motorcycle Club embraced the run with gusto. Run to the Wall was meant as a commemoration for those who served in Vietnam, living and dead, missing or present and accounted for. Now a new dimension was added to the bike run. Since increased attendance allowed for a fuller loop, 20,000 bikes presented in formation four bikes across and eight miles long. Most bikes carried an additional rider, for a riding total over 30,000. Beginning at the parking lot of the Pentagon, the cascade of thunderous unity proceeded all the way around to the bridge at the Arlington Cemetery, a fitting finish for the memorial run. Cheering onlookers lining the street waving flags of support visibly moved the hardened vets as they rode past. In a solemn finale, Medal of Honor recipient Gary Wietzal offered a prayer for those still missing. This, then, was Rolling Thunder II. But those who accused the federal government of doing nothing on the POW/MIA issue were wrong. Officials were in fact busily taking action. Unfortunately, the action taken was to move names off MIA lists into the killed column - not that any remains were being sought or unearthed. The game was more one of playing the odds, Pentagon style. If a POW did not turn up at the end of the war, passage of time increased the chances they wouldn't be showing up ever. So why waste time and money looking. This unconditional logic flew hard in the face of vets waiting for the chance to run rescues for those servicemen their Pentagon seemed to treat as out of sight, out of mind. Champions of the Lost From then on each annual event attracted greater numbers of vets, non-vets, bikers and non-bikers. But to call Rolling Thunder a motorcycle run is to grossly understate its impact. More and more, word got out that the various activists organizations affiliated with Rolling Thunder were the ones vets could turn for help in countless areas. Help with the small stuff - like who to call to get needed forms for the endless benefit jungle was hand in hand with bigger stuff, like how a family of a MIA could appeal the killed on paper status of their missing loved one. The Rolling Thunder movement had taken on a very real, very vital life of its own. Meanwhile, by 1991 the bike run just kept growing. The '91 Run To the Wall at Rolling Thunder IV was 45,000 strong, with an estimated 20,000 bikes taking part. Proudly flying the Stars and Stripes beside stark black POW/MIA flags, riders cut a striking picture as black leather on blue jeans met shining chrome in a deafening thunder of unison. By now the Pentagon north parking lot had become something like a reunion spot for vets young and old alike. Often it was the only time old war buddies saw each other, and every year more familiar faces appeared. Each mile of pavement held special meaning for the thundering vet procession. It began at the Pentagon, military seat of the nation. Up and over the Memorial Bridge they rumbled, to descend down the street past the Capitol, where political policy dictated the fate of American soldiers since before these riders were born. Waves of bikes rolled along Constitution Avenue, symbolic of the rights and freedoms they committed to die for. The route wasn't complete without a pass by the Commander in Chief's place on Pennsylvania Avenue where White House executive orders mean ultimate life or death for American servicemen in conflicts a world away. In solemn tribute the cavalcade finally reached the Vietnam Vets Memorial where speakers gave voice to absent patriots: Lost in battle. Lost in shifting policy. Lost in paperwork. But lost in the hearts of these proud Americans who fought beside them? Never. On Capital Hill, professional number crunchers predicted the whole Rolling Thunder "thing" would fade fast like the insignificant fad they considered it to be. Those who didn't see it fading away wished very hard it would. After all, this was just a bunch of disgruntled vets out in force to make a little engine noise, right? Maybe the group's greatest strength was that nobody could convince them they would never be heard. Or maybe telling them they were doomed to fail fired up their "never say die" American spirit. Whatever the reason, these guys, far from disappearing, just got stronger. Rolling Thunder VI (1993) took on international support, as bikers from other countries, including Australia, Canada and South Korea rode with the U.S. Over 50,000 motorcyclists made the run in 1994. With Rolling Thunder support, Delores Alfond, chairman of the National Alliance of POW/MIA Families and Dan Wood, president of New Jersey Forget Me Nots attempted to hand deliver a letter to President Clinton. The message objected to the wink-eye policy that administration adopted toward Vietnam's dismal lack of honest POW/MIA accountability. Blocked in their efforts to get the letter to the President, Rolling Thunder's leaders staged a roaring protest. As the bikes began to pass the White House, they slowed down, then halted when columns of bikes had filled the streets around the White House. For the next few minutes, the ear shattering roar of thousands of bikes revving their engines literally vibrated the windows of the White House.

Ironically the patriotic protest staged in support of the men and women who put their lives on the line for America each day was generally dismissed as just rabble rousing by a Clintonisquely charmed press. Like Grunts in the Long Mud By 1995, Rolling Thunder support reached such proportions that it gained incorporation status. Muller and Don Luker made the organization officially non-profit and the national chapter became reality. State chapters burst up across America in rapid fire the following year. All positions were deliberately set up as non-paid, voluntary status. By definition, each charter agrees to help vets in need from all wars or conflicts, and adhere to the strict ethics of volunteer-based practice.

Muller says that Rolling Thunder members, led by Ted Shpak (Rolling Thunder legislative representative) and John Holland, sweated word for word on a bill known as the Missing Service Personnel Act of 1993. The bill was to guarantee that the government could not arbitrarily kill on paper missing servicemen without credible proof of death. Muller said they were absolutely stunned to later see a bill they all had worked so hard on literally gutted by Sen. John McCain, a Vietnam vet and former prisoner of war. But like grunts in the long mud, Rolling Thunder volunteers never stopped pushing. It took two more years, but by 1995, in an effort to revive the original intention of the 1993 bill, the grunts had put together 20 resolutions to create the Missing Personnel Act of 1995. In 1997, despite McCain's efforts to again sabotage the bill, 13 of the 20 resolutions passed intact. Meantime, each Memorial Day weekend Rolling Thunder run broke the previous year's attendance record. Year by year the numbers of state Rolling Thunder chapters continued to rise. When bikers revved up their cycles for the millennium 2000 run, the echo from the thundering bikes was heard for miles. That run marked several milestones in Rolling Thunder's proud history. The astounding 250,000 in attendance equaled a full hundredfold increase over the first year's tally. That fact alone amazed both detractors, who thought by now the crusty vets would surely have lost interest and concern for their missing men in arms, and supporters, who hoped against hope that by century's end, America would have honestly accounted for its missing servicemen. The year 2000 run gained a higher profile by the presence of Miss America, Heather French, who dedicated her reign to homeless veterans. She took her pageant platform championing veterans' rights seriously. When the bright-eyed beauty led the Rolling Thunder ride with her Vietnam vet dad Ron French, she brought even greater public focus to the cause she cared about. Members note that TV media coverage of the annual event had also grown from a mere 4 ½ seconds the first year to 4 ½ minutes for the 2000 ride. Although less than five minutes in the spotlight might not seem like a lot, in media terms, that's a whopping piece of press pie. Generally ignored by mainstream press is Rolling Thunder's stand that since the end of Vietnam War, over 10,000 reports of sightings of live Americans in bleak captivity were documented. They cite an ominous tradition in the fact that since Soviet-U.S. relations blossomed, reports were unearthed that live Americans remained in Soviet prison camps after World War II. American POWs of the Korean War era fared no better, according to many official documents, Korean War vets were also left in captivity after that dismal war. No wonder, the vets claim, that an organization based on and for advocacy of the average serviceman was so badly needed. Rolling Thunder Continues to Grow Of course, some of the most important work Rolling Thunder does takes place far from the rolling cameras. During the 363 days between Memorial Day weekends, Rolling Thunder representatives lobby for laws which will ensure no American fighting men will ever be left alone on foreign soil after the shooting stops and the politicians shake hands. There's a tremendous irony in the fact that it is necessary to make it law for the military to account for its own. Muller notes with pride that Rolling Thunder joined POW/MIA groups to press forward the passage of a bill assuring that federal government buildings would include the POW/MIA flag in colors flown on national holidays. Journeys to far off former war zones like Vietnam are sponsored and staffed by Rolling Thunder efforts. Closer to home, volunteers regularly visit their local VA hospitals to bring meals, clothing, personal items and just old-fashioned companionship to hospitalized vets. Many of these patients have no visiting friends or relatives so the brotherhood of other vets is the only real family tie they enjoy. That it continues to grow in leaps and bounds says a lot for Rolling Thunder's success. The 39 state chapters in 2000 grew to 48 in early 2001. No one questions expectations that in short order every state in the Union will be fully represented by its own Rolling Thunder chapter. Still, Muller sees in its success a certain sadness. In Rolling Thunder Times, the organization's newsletter, he writes, "I am sorry to say that Rolling Thunder XIV will be May 27th 2001. That means there are still POWs unaccounted for throughout the world." A Few Old Vets Not Going to Shut Up and Not Going Away Each rider comes with a different face and personal reason for attending the run. That's true for every Rolling Thunder member, including Walt Sides, one of the founding fathers of Rolling Thunder. "I don't do interviews." Pretty much the first words out of Sides' mouth when he was first approached for this interview. His attitude gives proof to the way the retired Marine 1st sergeant regards his experience with the press. Sides learned his wariness of the media first hand, back when the movement first started, when coverage of the group was sketchy at best, and biased at worst. In the long run, Sides says, staying clear of the press has spared him a lot of grief from being misquoted. "If they've decided what they're going to print before they talk to somebody, why even bother interviewing them?" Far from being a holiday celebration, for Walt Sides, Rolling Thunder is serious business. "It's not a parade. It's a demonstration," he explains. To him the difference is important. At heart, he'll always remain the patriot loyal to his country, and declines to speak against any American president. "I'm 61," he notes, "and I don't remember any bad president in my lifetime - no president who's had a bad effect on me or my family. They're just people after all." Yet he admits he looks forward to improved treatment for veterans under the new Bush presidency. "I think we'll get a lot more for veterans from the new administration." He recalls bristling under other campaign rhetoric that touted the military as just fine the way it is. "Our armed forces need a good overhaul," Sides adds. A common misunderstanding of Rolling Thunder is that it speaks only to issues of Vietnam. Sides is quick to point out the many other facets of veterans rights' it champions. The Desert Storm syndrome is only one example of why vets need the voice of Rolling Thunder speaking out for them. "A lot of changes are needed in the VA, in the government's cover-up of Desert Storm's chemical effects on our men. It was 20 years owning up to the fact that Agent Orange undeniably affected Vietnam veterans. I'm one of them." He sees the same resistance to accountability in withholding help for Desert Storm victims seeking benefits. It takes a lot to wear down a war-scarred veteran. But if anything can do it, it's beating one's head against the wall of bureaucratic VA red tape year after year. And that's just what happens in case after case of weary vets too tired and sick to fight for their so-called benefits. For them, the sound of Rolling Thunder is a lot like music to their ears. Rolling Thunder remembers the POWS and MIAs left behind in wars the politicians want badly to forget? There'll always be those who wish vets like these would just shut up and go away. But as Sides points out, "Fortunately we've got some old hard core vets who're not going to shut up and are not going away." They Didn't Mind Losing a Few Good Men For a Little Glory A veteran of 21 years and two terms of Vietnam War service under his belt, Sides recounts a particularly striking Vietnam memory. "I remember my last tour in Vietnam when they announced the war was ending, and they'd be sending the troops home. Everybody was glad because we knew we'd be going home. But the battalion commander just kept sending us out and sending us out, trying to get us in a firefight. "I'd been in the infantry 12-14 years, so it was obvious to me he was trying deliberately to get us into firefights. I'll always remember when it came to me. I was standing up on this mountain in Vietnam and the realization hit me: There are commanders not above losing a few good men to get a little glory." For soldiers like Sides, the issue of accountability of military authority hits very close to home. "When the brass makes a mistake, they don't particularly want it advertised." Once home in the U.S., Sides - like many vets - put the experience behind him. "If I was in a room with say 30 people and the subject of Vietnam came up, I was out of there." But the lack of accountability for lost and missing servicemen eventually got the better of him. He says he came out of that closet of silence in the 1980s, along with lots of fellow vets. "I thought back to that day on the mountaintop," he remembers, being sent into the firefight for the advancement of some commander's career. Sides admits the practice is by no means new. During the Civil War, President Lincoln was notorious for allowing his generals to use U.S. soldiers like cannon fodder and there have always been problems with U.S. prisoners of war being abandoned. Still it seemed to Sides if our own government disavowed their existence, and if veterans didn't stand up for their own, who would? From a Mountaintop in Nam to Rolling Thunder in the Streets of Washington Sides gives credit to Ray Manzo for the thundering cycles through D.C. concept that has become the hallmark of Rolling Thunder's unity statement. His first meeting with Manzo left a lasting impression. "I remember it was a pretty sunny, warm day. I can still see him walking up the steps toward us." Sides was manning a POW/MIA vigil along with fellow veterans John Holland and Ted Sampley on the capital commons in an effort to get public support for the MIA and POW issue. It's an old truth that a Marine can always spot a fellow Marine, no matter how out of uniform or far away. Sides laughs that he picked Manzo as a leatherneck right away. "He looked just like a Marine climbing those steps," Sides claims, "kinda dumb looking, with a look that said: Boys, I need some help. He had an idea. Could we do a run of motorcycles for the cause? "We looked at each other and said: Let's do it!" Rolling Thunder Struck a Common Chord in the Hearts of Vets Despite the fact that neither Holland nor Sides were bikers, the idea seemed to be the right thing at the right time at the right place. "John had a lot of knowledge," Sides adds, referring to Holland's expertise in getting things done in D.C. But where would the bikers all come from? "Ray said if we could set it up, he'd bring the bikers." And bring the bikers he did. The fledgling group split up the work, contacting the parks service, getting permits and printing up flyers. It would be some nine months later that the rugged Marine's dream became Rolling Thunder. From as far away as Oregon and California they came, from back country dusty hollows and big bustling cities, some came alone, some rode in cycle convoys. Many joined up as they met on the long road to Washington, and rode the rest of the way together in one common goal. Rolling Thunder had somehow struck a chord in the hearts of vets everywhere from all walks of life. That year the bikes first ran, it was hard to count the numbers roaring into D.C. from America's heartlands. "We thought 2500 bikes on the first run was a whole bunch," Sides explains. Little could the Rolling Thunder's founding fathers know then the movement would grow each year to the expected 200,000 in 2001. "Each run it's gotten bigger and bigger and bigger." As Rolling Thunder expanded, so did its support base. Where at first veterans had to stick their necks way out to demonstrate for their own, now a good part of the riders are civilian. Thousands of Americans come out to give very public thanks for the sacrifices of veterans like these, as well as those not yet accounted for. So what keeps vets like Walt Sides from just packing up and quietly going away? According to him, it's pretty simple: "If we turn and walk silently away, nothing will ever change," he maintains. "That's why we can never just turn and walk away." All in all, pretty eloquent words for an old retired Marine, who doesn't give interviews. |

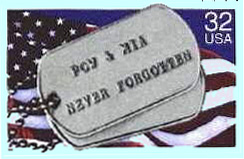

According to Muller, winning government approval for the

POW/MIA postage stamp in 1995 marked an important triumph for the

group. But the more members joined in the cause, the more work

there was to be done. They learned political hardball knows no fair

play.

According to Muller, winning government approval for the

POW/MIA postage stamp in 1995 marked an important triumph for the

group. But the more members joined in the cause, the more work

there was to be done. They learned political hardball knows no fair

play.